So I’ve migrated to a new site. Or, more precisely, I’ve migrated the old blog to this address, leaving the old jefferykrit.wordpress.com address as the start of a new personal blog. My reasons for doing so can be found there. In any case, this blog will not be updating anymore, so if you want new stuff from me head on over there! And if you find any broken links here, let me know and I’ll fix ’em!

Category: Uncategorized

Ode to January

Well, it’s that time of year again. The time of year where everyone gets super-depressed because the holidays are over and now all we have to look forward to is a month of cold, dreary, boring winter, broken up only by a weekend of mattress sales disguised as honoring our civil rights pioneers. I bet if you took a poll, most people would list January as their least favorite month of the year (maybe tying with September for many students).

I disagree.

January is one of my favorite months of the year. It’s not because I love skiing or sledding or any of that. It’s not because I love freezing to death because the maintenance crew at my apartment complex hasn’t gotten on the ball to fix my heater yet. And it’s not because I hate the Christmas season and just want it to be over (which I don’t).

It’s because January represents all the best of what’s great about humanity.

Think about it. In ages past, at least in temperate climates, winter was a time of apprehension and fear. A family would hope and pray that the harvest earlier that year was bountiful enough to get them through the lean months. All people could do was huddle in their shelter for warmth until spring arrived, hoping that sickness or cold wouldn’t kill too many of them, waiting for the weather to grow warm enough to begin planting crops for the year ahead. The world had to shut down because it was too cold and snowy to do anything productive.

But now?

January isn’t the month anymore where everyone huddles in front of the fire, waiting for spring. January is the month where the house is cold and empty, because everyone is out in the world pursuing their schooling or work, and making their hopes and dreams into reality. Technology has advanced enough that we can actually afford to go out into the world and stay warm, and keep living our lives without worrying about running out of food, or catching pneumonia and dying.

January is the time when humanity starts working. People go to work, plan out their year, and start their business back up. People bid their families goodbye and go back into the world so they’ll have a family to come back home to. Content creators start making things again, after weeks of hiatus. TV shows start up again, websites start updating, news programs stop talking about holiday stuff and instead focus on what’s actually going on in the world. Performing groups stop preparing the hundred or so works (and innumerable variations on those works) focused on Christmas and instead can pick from everything else available in the world!

If anything, we’ve compressed all of what used to be winter activities into the last part of December, where everyone gets together to spend time with loved ones and remember the old year. But instead of staying indoors for three months, we almost immediately turn around and start living again.

January is the default. January is the time when we define what we are. January is where we set the theme for the year, that all other months are simply variations on.

February is January with a night of candy and chocolates thrown in somewhere.

March is January with a night of drinking (or leprechauns; whatever’s your poison).

April is January with lighter jackets and a week off (depending on what you do for a living).

May is January with greener grass.

June is when we take a break from January because we’ve been doing it for five months.

The environment and seasons may change during all these months, but the activity remains constant. January is where we begin everything, where we define ourselves.

January is humanity’s way of saying to the world, “You know your suggested start time of March or April? Yeah, you can take that suggestion and shove it! ‘Cause we’re good enough and advanced enough to take literally the coldest and harshest month of the year and make it one of activity, production, and progress! We don’t hide in caves or cottages anymore! We are masters of ourselves! We can accomplish great things! And we’re going to take this entire month and lay the foundation of the universe!”

So let’s love January. After all, without January, what would there be to celebrate during the rest of the year, other than crops and pneumonia?

Ten Years of Bloggin’

Ten years ago today, I started a subsection on my Angelfire website dedicated to the Chip ‘n Dale Rescue Rangers character Monterey Jack to just act as a sort of online journal. The first entry consisted of a picture of my head from my mission (seen above), a description of a random murder mystery thing happening that day, some rambling about starting a blog, and a quote from President Boyd K. Packer about music that I used to have on my AOL Instant Messenger bio.

Now, my face is a bit older and chubbier, my Angelfire site is basically gone, I haven’t been active in the Rescue Rangers community for several years (ever since it became obsessed with My Little Pony), Pres. Boyd K. Packer has passed away (this actually happened, like, last week; they haven’t even had the funeral yet), and I probably haven’t used AOL Instant Messenger for about ten years. But this blog has kept chugging along, though the entries have gotten far longer and more sparse since the beginning.

The last time this blog had an anniversary (five years ago), I mostly took suggestions from readers and did a completely random post. During the first five years most of my posts were fairly short and random: small thoughts, online quiz results, pictures I liked, and so on — basically, everything that people do on Facebook now (here’s a good example). In a post-Facebook world, however, those kinds of posts dried up and moved to social media, so instead of short pictures or fun little things, this blog evolved into giant essays, mostly regarding dating, religion, and/or philosophy derived from video games.

It’s kind of interesting, for me at least, to go back and look at some of those earlier entries. I haven’t felt like I’ve changed a whole lot over the years, but reading the stuff I was writing ten years ago definitely shows a younger viewpoint. Some of the problems I was having are still the same then as they are now (singlehood, in particular, has always been a staple topic of this blog), though my approach to them has definitely matured over time. Compare an early entry where I was mooning over Kim Isom like a lovestruck puppy (even though I still never contacted her literally until her wedding reception), to a recent entry where I finally decided to be proactive in my dating life. True, I’m still single, but I like to think that at least I have a more mature outlook about it now.

I think the biggest shift occurred around this entry (the post right after the five year anniversary, interestingly enough) which is when I finally graduated college. Nearly every entry after that is a big long analysis of something, whether it be gingers, Glenn Beck, reactions to terrible robberies, LDS culture and alienation (if you really want to know why I’m taking a break from the Church, that article is a good starting point), or even an in-depth analysis of why I make in-depth analyses. Not that nothing before that date was philosophical or rambly (or both), but I seem to have focused a lot more on that for the latter half of the life of my blog so far, which is also why I’ve made a lot fewer posts in the past five years than the previous five (44 posts after that one vs. 202 before, not counting the 64 posts that I copied from my childhood journal).

In any case, I’ll continue blogging on occasion into the future, mostly about topics that will probably not be of any interest to the vast majority of readers, but sometimes about raw emotional experiences that change people’s viewpoints about either me or the world. Pretty much just like how my life usually goes.

To close, here are some random stats (at least since I moved to WordPress in 2007):

- 29% of my views have occurred on Saturdays

- I’ve had over 80,000 views from nearly 16,000 unique visitors

- The most views I ever got on a single day was March 20, 2013, when I got 1,062 views. This is especially baffling as I didn’t publish anything that month, and my most recent post at the time was a fluff piece about the TV show Arthur.

- My top five commenters have been (in order): Johnathan Whiting, Kjersti Parkes, Marné Lierman, Haley Greer (now Smedley), and Nate Winder.

- My most popular post: The Third Date Dump, with 12,033 views. I guess I coined a phrase? Or is it due to the link to an article on oprah.com that’s in it? Yeah, probably the second one. It’s still pretty impressive, especially since it was posted years after the runners-up:

- My second most popular post: the results of my Myers-Briggs personality test, with 11,918 views, though more than 9,000 of those were in 2010, probably by people just looking for the test itself, or possibly just a picture of Michael Jordan or Frederic Chopin (since 2012 it’s averaged about 55 views a year).

- My third most popular post: Mickey Mouse trying to commit suicide, with 4,922 views. I don’t quite know what to make of that.

- My fourth most popular post: The meaning of Tarantella, with 3,127 views. Probably mostly from students studying the poem in classes.

- Fifth and beyond are pretty close to call.

Happy tenth anniversary, blog.

Generation Geocities

So there have been a bunch of articles written recently about a certain age group that has been struggling to pin down its own identity. Caught inbetween the cynicism of Generation X and the hopeful optimism of the Millennials, this group hasn’t been able to embrace the ideals and concepts of either side. These are the people born between about 1978 and 1983 or so (or everyone who was college-age when 9/11 happened, basically). I like to define it in my personal life as everyone between my sister Annelise (who was born in 1976 and is most definitely a Gen Xer) and my good friend Sheldyn (who was born in 1985 and is quite Millennial). I have aspects of both of them, culturally speaking, but I can’t really say either of them are of “my generation”, even though fewer than ten years separate the two. And though you may not know either of the people I’m talking about, if you belong to this group you can probably think of people you know that were born in those years and probably feel the same way about.

As a member of this group, I identify pretty well with most of the points listed in those articles linked to above. As a kid we had computers but not the Internet (unless Prodigy or AOL counts). As a teenager the Internet existed, but was still in its primitive stage (the whole thing looked like this, basically). And as a college student everything was a giant mishmash of technology as the world struggled to adapt to the innovative revolutionary advances that had just become available but hadn’t settled down in a streamlined format yet. Everyone in my freshman dorm had a computer, but almost nobody had a laptop, and those that did have one had ones where the battery life was 2 hours, tops, and there was still no wifi, so they had to cluster around the ethernet ports scattered about campus with their network cable like hobos huddling together for warmth. Culturally we weren’t as white-bread peppy as those after us, what with their “High School Musical”‘s and their “Katy Perry”‘s and so on, but we weren’t quite as angsty as the Nirvanas and Nine Inch Nails of the early-to-mid-90’s, either. These articles go pretty in-depth about where we “fit”, culturally and technologically speaking, so I won’t rehash it all here.

What I find most intriguing, though, is an unspoken thread woven throughout these articles. Every single one of them has been written by someone in that generation! Most people on either side of us lump us together with either the Gen Xers or the Millennials, even though some of those articles are a few years old. There has not been a cultural zeitgeist to unify us other than through negative space that nobody else can identify. All the other generations have been named fairly early on and by those outside it: the name Generation X was popularized by a writer of the baby boomer generation, and, oddly enough, both Millennial and Generation Y (the previous name for the Millennials that never quite stuck) were also coined by baby boomer writers. And good luck getting anyone not inside this group to care about it: I have talked to baby boomers, Gen Xers, and Millennials, and none of them really care about or can even identify with our lack of definition. Gen Xers just see how tech-savvy we can be sometimes and lump us in with the Millennials, whereas Millennials see how familiar we are with a pay phone (or some other similar obsolete technology) and push us upstairs to a previous generation.

We have to define ourselves because nobody else will define us.

Even within the group, however, we’ve had a hard time pinning down what we are. Every one of those articles give completely different names to our group (Xennials, Generation Catalino, the Oregon Trail generation, “The Lucky Ones”, and so on), and almost all of them list entirely different cultural touchstones that define us, though they agree much more on what the previous era ended with and what the next era began with. There also seems to be a bit of a divide on whether or not we are a lucky/good/happy generation or an unlucky/terrible/cynical one. This, I think, relates to everyone else’s lack of concern about defining us. People are notoriously myopic about their own composition and identity. What’s important in one person’s upbringing may be a complete unknown in somebody else’s, and without someone on the outside saying, “This is an important cultural touchstone to this group,” it’s hard to come up with a consensus on what defines us. We’ve got “This is what we aren’t” down pretty well, but the “This is what we are” has yet to be pinned down, assuming that it can be.

But really, in the end, isn’t that our true defining characteristic? That we can’t be defined? We keep saying, “We’re a bit of this and a bit of that, but we’re not all this or that.” We’re tech-savvy, but not beholden to technology. We appreciate cynicism without embracing it. We’re optimistic, yet wary. We define ourselves by both our nostalgic past like Gen Xers, and our bright future plans, like the Millennials (as a side note: my personal belief as to why Millennials aren’t defined by their nostalgia is because the kid shows of the late 90’s and the pop culture of the early 00’s wasn’t worth being nostalgic about, as most of it was pretty terrible). So far, our search for a cultural identity is our cultural identity. All we know is that there’s something that separates us from those above and below, even if we don’t know what it is.

Our era was characterized by old meeting new. Everything was a giant hodgepodge. You could ride your bike wherever you wanted to around your neighborhood, but you still had to buckle your safety belt. Fax machines and pay phones coexisted with instant messaging and email. You could get on the Internet anywhere, as long as you had charged your laptop and could find an ethernet port to plug into. You couldn’t instantly share photos with all your friends, but you could share your terrible Geocities site filled with animated GIFs, blaring MIDI files, and goofy quotes. Heck, for the first few years of this very blog it was hosted on Angelfire, of all places. Angelfire!

That’s why I propose the name “Generation Geocities,” not just because Geocities was a thing when we were coming of age, but because Geocities represents what we really are: the prototype generation for the new social and cultural revolution. In Geocities you could see the beginnings of what the Web would become: people trying to share their lives and interests with their friends (and potentially complete strangers), yet it didn’t have nearly the power and panache of Facebook, or Instagram, or Pinterest, or whatever social media platform you prefer. It was untried and raw. Everybody’s website looked terrible, but at the same time everything seemed much more personal and sincere, since market research, SEO, and other business practices had yet to be invented or adapt to the new web-based way of thinking. That’s why that Space Jam website I linked to earlier looks like it was designed by a 12-year-old: the playing field was level. Nobody knew what was going on.

So in comes our generation, not steeped in the non-computer traditions of our forefathers, yet old enough to be innovators ourselves. And so we grabbed onto Geocities as ours. We latched onto AOL Instant Messenger as ours. Napster, dial-up, ska music (remember 1997, the summer of ska? That was ours.) — all things that we thought were great, yet lasted for only a brief instant. Somebody had to be the ones who defined themselves with this new technology that no longer exists. Everything that could have defined us was so quickly superseded by more streamlined and professional versions of itself that almost nobody outside of our demographic even remembers them anymore. Compare this to today, where Facebook has been virtually unchanged since at least 2007. Sure, the layout has changed several times, but at its core it’s still the same basic deal. Smartphones have been the same on a fundamental level since the first iPhone came out. I’d say that the last fundamental game-changing technology that has come out has been the smartphone, and most of the gadgets that have come out since then have been tied to it in some way. As a result, technology has been somewhat stagnant. Culture has been the same way: nostalgia is such a big thing for Gen Xers that the Millennials and the rising post-Millennial generation are basically just living through the exact same TV shows and movies as their parents. Movies are now multi-part epics that span several years. Things have staying power now. Everything has been polished and streamlined.

Geocities represented something new and untried; rough and full of promise, yet so quickly obsoleted by something better that it barely registers as a blip on the radar, and nobody that wasn’t involved with it even cares that it existed, except to note the newer thing that it led to.

That’s us.

And maybe the reason that nobody else cares about our identity is that we have none that nobody cared about but us. All we know is that we’re different.

We’re not quite breakfast. We’re not quite lunch. But we come with a slice of cantaloupe at the end. You don’t get everything you get with breakfast or lunch, but you get a good meal.

Test Post for music

I’m trying to find a good host for MP3s since my old one went belly-up. Let me know in the comments if this song plays for you:

Is there a Doctor in the house? (Attempt #6,924 to get into Doctor Who)

(Note: this post will contain spoilers(!) for the Doctor Who 50th Anniversary episode “The Day of the Doctor”.)

So over the years I’ve had quite a love/hate relationship with Doctor Who. I’ve tried to get into the show several times, but every time I try it’s never quite grabbed me like it seems to have grabbed about 80% of nerds (especially female nerds) I talk to nowadays. I’ve tried exploring exactly what about the show that drives me crazy, but I’ve never been able to correctly pinpoint it (and whenever I’ve tried, somebody on Facebook has always pointed out why my opinion is wrong and why I should feel bad for having it). I really, really, have wanted to like the show (for one thing, it would make my dating life easier), but sometimes you just don’t like something despite all indications that you should (coincidentally, something that’s also applicable to my dating life). But every so often, I watch another episode or special or what-have-you to see if this one is the one that makes me say, “Yeah, OK, I can overlook its flaws; it’s a good show.” It is in this spirit that I watched the much-anticipated 50th anniversary episode “The Day of the Doctor”. Has it changed my mind about the show?

Well, no. But I think it’s helped me figure out why.

Let me be fair: I absolutely loved about 60% of the special. All of the Doctors were great (John Hurt included) as well as, surprisingly, Billie Piper (which is no mean feat because I hated Rose. It’s clear now that that was more due to the character herself than the actress, as she did a fantastic job here as “the conscience”). The other characters ranged from adequate to embarrassing (but I’ll get to that in a minute). The special effects showing the actual Time War and the devastation being caused all across Gallifrey were (mostly) amazing as well. As for the writing, most everything concerning the main plot of the special (that being the fate of Gallifrey and what exactly he did to end the Time War) was great. The no-win scenario has been examined many times before in fiction in general and sci-fi in particular, and it’s even more compelling when 1)it’s on such a huge scale, and 2)technically we’ve already been dealing with the aftermath of what happened for eight years already. This has been such a central part of the Doctor’s character throughout the entire post-reboot story that the dilemma has a lot of weight to it and it has shaped who the Doctor has been, even if it’s been ever so subtle. Probably one of my favorite moments in the entire special is when Ten and Eleven are being their goofy selves and the War Doctor asks why they act like children when they should be acting grown-up. And they both just give him a somber look. No words are needed, because the answer is both obvious and heartbreaking. I’m glad they got a completely different actor to be that Doctor instead of just making it Paul McGann or something (though I like Paul McGann, don’t get me wrong) because of the symbolism. The War Doctor is really the protagonist of the story, and Ten, Eleven, and all of the other players are really just acting in a morality tale for him (up until the ending at least). Even a fair bit of the lighter stuff worked pretty well, like the bit where the three Doctors are trying to figure out how to open the door via the most ludicrously complicated method ever, only for the door not to be locked. And the ending was fan-freaking-tastic.

It’s when we get away from that central story and the themes surrounding it that the special starts to fall apart (for me at least). There were two major flaws here that perfectly illustrate why I haven’t been able to get into the franchise as a whole.

First of all, the monsters. I’ve never seen an episode where the monsters have been truly terrifying or, indeed, have been able to take them seriously (though “Blink” came the closest). Take the Zygons in this story. First of all, they look stupid. Second, their motivations aren’t all that clear other than “let’s take over Earth for some reason!” Third, their particular dilemma is resolved in a typical Doctor Who way that I hate: the Doctor(s) point their screwdriver(s) at something, causing the plot to be instantly resolved! And in this case, the resolution (causing everyone in the room to forget whether they’re Zygon or human) doesn’t even make sense, both in logistics (oh no! I can’t remember if I’m human or not! Oh wait; can I turn into a red tentacle monster? I can? I guess I’m a Zygon then!), and as a means to resolve the plot (well, since I can’t remember if I’m Zygon or human, I guess I’ve lost all my ambition to take over the world, plot over). I know that in this particular case the whole Zygon thing was meant mostly to set up some MacGuffins as well as draw some parallels to the main plot (which actually worried me: I was afraid that somehow the Doctor(s) would get the idea to mindwipe all the Daleks in the same way or something equally stupid).

The problem is that so often the focus of Doctor Who episodes is on the silly monster of the week and the weird dilemmas that they cause for our heroes (and very few of them are much better than the Zygon story here) that I can’t take them seriously, even if there’s good character stuff in between the lines. The Daleks especially suffer in this regard, and the only moments I was pulled out of the story happening on Gallifrey were when the Daleks themselves were onscreen, slowly milling about yelling “EXTERMINATE!” You know, you can give a squirrel a machine gun, have him go on a murder spree, and give him the dialogue of the Joker, but at the end of the day he’s still just a squirrel with a machine gun and on a certain level he’s going to be impossible to take seriously.

Let’s take a parallel example from Star Trek. In the first season of The Next Generation the creators of the show had built up the Ferengi to be the Big Bad Guys that our heroes had to contend with, much like the Klingons had been in the original series. But when the episode that first featured them aired, it became clear that these villains were not threatening at all, what with their resemblance to little goblins, and their flapping arms like the flying monkeys from The Wizard of Oz, and their silly laser whips, and just their overall goofiness. So the creators, seeing that they weren’t working as villains, slowly morphed them into comic relief (for better and for worse), and instead introduced the Borg in the next season to be the real threat. I feel that Doctor Who‘s approach would have been to feature the Ferengi in thirty more stories and have everyone talk about how horrible they are (and maybe even show them killing some guys and whipping some children and drowning poodles or something), even though they still look like silly monkey goblins.

When Doctor Who gets away from the Monsters of the Week I think it usually does much better. For example, a recently-recovered second Doctor episode titled “The Enemy of the World” (which I haven’t actually seen, but I did watch a fairly thorough review/recap of it) features the TARDIS crew landing in the year 2018, where a dictator named Salamander (yeah, I know) who resembles the Doctor is in charge, and the main focus of the plot is whether they should support the rebels opposing Salamander or not. I thought the plot was engaging, and the clips that I saw looked pretty good (mostly thanks to Patrick Troughton’s fun take on both the Doctor and Salamander), to the point where I’d like to watch the episode itself if I can find it. There are no Daleks, cybermen, or any other alien threat; just people.

Speaking of people, this brings me to the other major flaw that keeps me from really getting into the show, and I freely admit that this one’s a little more subjective, but the way the show often handles historical figures irks me quite a bit. In this particular special the whole plot with Elizabeth I was one that I found insufferable (and not only because it tied into the dumb Zygon plot). Often it feels like the historical plots in Doctor Who play out like somebody’s weird fan fiction. “Hey, let’s have the Doctor go meet Queen Elizabeth I because he’s a time traveler and all that! Of course she falls in love with him because he’s just awesome! Also, there are aliens! Oh, and the Doctor also helps Vincent Van Gogh overcome some personal demons (and aliens!) and when he battles some ghosts (or, more accurately, ghost aliens) in Victorian England of course we have to have Charles Dickens help him because it’ll be cool!” I know this type of plot doesn’t happen all the time but it does pop up quite a bit (especially since one of the core tenets for the show at its inception was to teach kids about history) and it’s just silly. Quantum Leap had a rule that Sam Beckett would never leap into or interact with anyone famous (except for maybe a quick cameo), to avoid this kind of silliness (a rule which the network made the writing staff break in the last season to try to buoy up sagging ratings, which resulted in some pretty stupid episodes like Sam leaping into Elvis). Even Star Trek, with its myriad of time-travel stories, usually avoided the “cast meets historical figure and hilarity ensues” plots unless they were their own made-up historical figures like Zefram Cochrane (the sole exception I can think of is when they met Samuel Clemens, and that wasn’t a very good episode anyway). It also doesn’t help that usually these historical figures in Doctor Who are written with the same sensibilities as late 20th-century or early 21st-century British people.

There are a few other minor niggling things about the show that irk me (such as the “ooh, the Doctor’s in town; excuse me while I swoon and ask him to take me to the moon for lunch” opening we had here, which most recent companions have a variation on. Which is a shame because, aside from that scene, Clara seemed to be a solid character, even though I haven’t seen any other episodes with her), but those two are the big ones, I think, especially the first one. And it’s clearly a subjective thing: obviously most Whovians are able to take the Daleks and other, sillier aliens (such as the Slitheen, which probably turned me off to the show faster than any other single thing) more seriously than I can, or at the very least overlook these problems; but as much as I’ve tried, I can’t. It’s like the problems I have with anime: as much as I try to enjoy the great story and/or characters of many animes, I can’t get past the problems I have with the art style and limited animation.

It’s a good show. I just can’t get into it. Sorry, guys. Now please tell me why I’m wrong.

25 Things that Drive Me Crazy About Buzzfeed Lists

There have been a lot of lists popping up on Facebook lately: the top 25 things you’re sick of hearing when you’re single, or signs that you’re an introvert, or reasons that <insert washed-up teen star> shouldn’t have been allowed on <insert music awards show> while doing <insert made-up word that apparently all the darn kids these days are using>. But there’s something wrong with these lists…:

1. Animated GIFs

Every one of these lists is full of animated GIFs, usually of celebrities making weird faces or being sassy. C’mon, internet. Haven’t we grown since 1996? Your point gets across just as well without a picture of Snooki gasping, especially if the “animation” is the camera moving slightly to the left, then resetting every three seconds.

2. Uhhhhhh….

Actually, that’s it. The lists are inoffensive otherwise. It’s just those horrible GIFs that make all these lists look like they were put together by a fourteen-year-old girl on Geocities. I just had to get that off my chest.

Poison Ivy Mysteries: Low art?

Recently a few reviewers posted some reviews of the most recent Poison Ivy Mysteries show (the second run of Justice at the Gold Dust). The reviews were all over the map, but one of the reviewers in particular was criticizing the show for being simply a bunch of stereotypes strung together; in her words, “[the script] seems to be constructed over a thin veneer of tired wild west tropes – the lusty barmaid, the crooked mayor, the ingénue, the tomboy, the leading man, and the town drunk are all present.” Annelise’s rebuttal to this sentiment – that the characters were flat and boring simply because they were easily recognized – states, in essence, that the types of murder mystery shows she writes can’t get too complicated or the audience will get lost. Annelise has also said elsewhere that PIM has actually attempted to do a show where the characters were a lot more complicated and three-dimensional, with the end result being that most members of the audience had no idea what was going on (I believe the show she was referring to was Club Mystique, our 1940’s detective show). I’m not going to rehash her arguments here, but one of her points was that murder mystery dinner theater shows put on by Poison Ivy Mysteries are meant for pure entertainment, and should not be compared to works that strive to do anything more. This has been true so far. But it got me thinking: could we?

Would it be possible to produce a fun, entertaining murder mystery that also speaks to the human condition, or whatever else this particular reviewer was looking for? Can we write a show that is also considered “art”?

What is art, anyway? The broad definition is basically any work expressing the imagination of the creator, which could be almost anything, ranging from the illegible crayon drawing a six-year-old made that he says is a car, to Cristo putting up fabric in Central Park just because it looks cool, to Stanley Kubrick telling a story about human evolution that takes as much effort on the part of the viewer to understand as it does the filmmaker, to a story about an overweight plumber rescuing a princess from a fire-breathing turtle king. However, I believe that when people ask the question “what is art?” they are more likely referring to what makes “high art” or “true art.” Or, in other words, what defines a work that people can say have had a significant influence? What rises above the 90% of everything else that is crap (it’s a law, look it up) to stand out as highlights of their respective mediums? What separates Citizen Kane from Transformers? The answer to this question is multi-layered and complicated (and changes radically depending on the medium being discussed), but for my purposes I will say that true art will make the audience think. And not simply think in terms of comprehension or analysis of plot elements (or following the bits and pieces of a murder mystery), but challenge an audience member’s conception of the world around them and make some sort of connection.

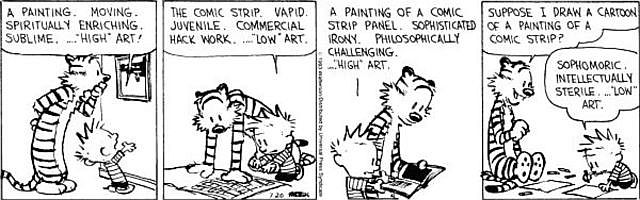

Take the Calvin and Hobbes comic strip I posted above. This strip was published in the Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book, along with this comment by Bill Watterson: “I would suggest that it’s not the medium, but the quality of perception and expression, that determines the significance of art. But what would a cartoonist know?” The great irony in this statement coming from that source is that I think most people today would consider that Calvin and Hobbes demonstrates some of the very best qualities of newspaper comics, and even now, nearly twenty years after its last strip, is still hailed as a standout among its peers. It’s not just good, it’s art. Bill Watterson and a few others, such as Gary Larson and Charles Schultz, took a medium that most people considered to be nothing more than pure entertainment and elevated it as a form of expression.

What defines the quality of perception and expression of a theatrical piece? Some may say it’s novelty. Others may say it’s tackling important issues. But I believe it has to do with one important concept: how well can I connect to these characters? For Poison Ivy Mysteries in particular, it comes down to avoiding the Eight Deadly Words:

“I don’t care what happens to these people.”

We are lucky that, because of our chosen murder mystery format, most people want to pay close attention to the plot and characters simply because they actively want to solve the crime. Video games have been getting away with this for years because the level of audience participation means that less care can be given to fleshing out characters, plots, and settings than in a typical passive medium such as a movie, play, or TV show, while still leaving the participant satisfied at the end. Most people care what happens to our characters because they want to figure out the mystery at the end, not necessarily because they care about them as characters. But that doesn’t mean we can’t pull a Portal 2 and make a fun game with great audience participation that also happens to have engaging characters in it. (Portal and Portal 2, by the way, I would consider “high art,” though I know plenty of people who would dismiss them due to the medium.) I would say that the more we can get the audience to care about these people, the better the shows will be.

Poison Ivy Mysteries scripts have been fun, witty, well-plotted affairs with clever interactions and wordplay, with interesting mysteries to solve. They are good, if not excellent, shows. However, it is true that most of our shows have been pretty shallow in order to facilitate understanding for the audience. And I’m not going to pretend that Justice at the Gold Dust is an exception to that rule. It’s not. The characters and setting are old wild west tropes and little else. (Which is not a condemnation; Tropes Are Not Bad. A relevant quote from that page: “Indeed, a trope, however unrealistic, can be a convenient shorthand when played straight; setting up aversions or subversions for it can be more wordy than is needed to get on with story.”) It’s gotten to the point that internally we’ve begun referring to each show by a truncated name, based on what stereotypes it embodies, Friends-style. The Sci-Fi show. The Western. The Hollywood Show. The Medieval Show. The Wedding Show. I like all of these shows (some more than others), but I don’t know if anyone would consider them art. However, there is one show we’ve done, and two characters in particular in that show, that demonstrate that it is possible to do more complex characterization that challenges the audience to face some of their preconceptions and maybe even think a little, thus turning this show into my favorite out of all the Poison Ivy Mysteries shows so far (yes, even more than the sci-fi show).

Curse of the Scarab, on the surface, seems to be simply another show filled with stereotypes, this time from the 1920’s, and in particular the Egyptology craze that was going on at the time. The characters seem to be your basic stock characters: the eager cub reporter, the stuffy curator, the wealthy dowager, the “legitimate businessman” (aka mob boss), the adventurous tomb raider, and the somewhat nerdy researcher/assistant to the curator. The gimmick of the show, however, is that partly through the evening, an ancient Egyptian curse starts striking members of the group at random, causing strange and often debilitating effects upon them. Most of them are just plain silly and a lot of fun to see. The mob boss suddenly becomes scared of everything, the curator has to walk backwards, the dowager regains her youth, and (my personal favorite) the researcher suddenly has an unseen barbershop quartet repeating everything he says. These are all fun to watch, but by the end these characters are all pretty much the same going out as they were coming in. Not so for the final remaining two characters.

The adventurous tomb raider is a woman who has been trying to make it in a man’s profession in a man’s world (especially considering the time period in which this show is set). She’s also involved in a love triangle with the reporter and the researcher (she likes the researcher, the researcher ends up liking the reporter, and the reporter just wants the scoop!). However, her curse ends up turning her into a man (in a very fun song). This, of course, complicates the love triangle to no end (represented in another fun song), but more importantly, suddenly she/he has fulfilled one of his/her wishes: being treated like an equal by men. In fact, the curator, who up to this point had been belittling her to no end, suddenly has great respect for the man she has become. This is interesting for two main reasons: first, usually the gender-swap plot goes male-to-female, not the other way around, so it’s already got a bit of a twist to it. Second, while some of the typical gender-swap tropes are present (up to a point; it’s a family show!), such as complaining about how she’s now balding, her focus is more on “will being a man *actually* help me gain the respect I wanted from my peers? Or did I already have that respect from those that matter? Is there truly anything worth doing as a man that I can’t as a woman?” An intriguing question for the 1920’s, but even more relevant in modern times (especially since the character was written by a successful female businessperson).

It’s a question to think about.

How does her character arc end? More importantly, how will she change as a person through this experience? I can’t answer these questions without spoiling the ending of this particular show, but rest assured that even though her time as a man is temporary, she comes out a changed person.

The cub reporter, for much of the show, is still pretty one-note. She’s looking for the scoop, trying to write a great story that will land her a career as an actual successful journalist (currently she works for Vanity Fair), oblivious to the flirting that the researcher is throwing her way. However, her curse (which is the last one of the evening) is to be unable to think anything without saying it out loud. In other words, she begins repeating her inner monologue. And this inner monologue, while still concerned with landing that big story, also begins rambling about her mixed feelings toward the researcher, her doubts in her own talents as a reporter, and her fear of what the evening is turning into and the danger they’re all in. In other words, the opposite of everything the character had been portraying so far. And with these revelations, suddenly she becomes so much more interesting, not just as a piece in the mystery, but as a character. She’s not a stereotype anymore; she’s a person, and while her personal plotline never really gets resolved by the end and it’s not clear whether she’s been changed by the experience like the tomb raider was, the audience can feel like they’ve gotten to know a person and all that comes with her, instead of just writing her off as another stereotype.

Does this make Curse of the Scarab “art”? Maybe, maybe not, but it certainly takes some steps in the right direction. These two characters illustrate some pointers that I think will help PIM murder mystery characters become more than stereotypical tropes put together.

1) Introduce interesting issues that the characters need to grapple with. These needn’t (and probably shouldn’t) be the focus of the show, as that may quickly complicate the murder mystery part to the point of hopeless confusion (a la Club Mystique). The tomb raider’s core issue had nothing to do with the main plot of the Egyptian curse and the later murder (though the love triangle part may have been either a clue or a red herring; I won’t reveal which), so the audience members who didn’t really pick up on it didn’t have to in order to get the main point of the evening. But raising some of these issues on the side will make certain members of the audience sit up and take notice, and have something to think about on the ride home apart from “whodunnit?”

2) Make at least some of the characters dynamic. The tomb raider had quite a different outlook by the end of the show than she did at the beginning, even though she was still fundamentally the adventurous Indiana Jones-type. Static characters (i.e. those who are basically the same at the end of the show as they were at the beginning) are not bad, but making all the characters static is. And making one character fall in love with another character (with all the associated tropes) isn’t enough to make an interesting dynamic character. Some of the more fascinating onstage relationships to watch are how dynamic characters are changed by the static characters that come into their lives and mess it up. How Oscar is changed by Felix, or how Valjean is changed by the bishop, and in turn becomes the static character effecting changes in others. (Incidentally, Javert is my favorite character in Les Miserables (Russell Crowe notwithstanding), mostly because during the entire show he is a completely static character, but subtly Valjean has been turning him into a dynamic one by the end, and that entire character arc I find fascinating. But I digress.) Other than falling in love, most of the murder mystery characters stay the same throughout most of the shows that we’ve done. This is partly a writing problem, but also partly an acting one, as some of the changes to the characters as written in the script do nothing to change the actor’s performance of said character throughout the night. (Possibly this was better with the tomb raider character because she was played by two different people.) This brings me to my third point:

3) Subtext, subtext, subtext! This is not a writing problem, this is an acting and directing one. The cub reporter in Curse of the Scarab ends up speaking her subtext as regular dialogue, and therefore it fleshes her out as a character. However, it’s entirely possible to give a performance depth by adding subtext to it without the script spelling anything out. Take, for example, the two runs we have done of Death: The Final Frontier (aka the sci-fi show). (Spoiler alert, by the way!) There is a redshirt ensign who, on the surface, seems to be just this goofy guy who’s always trying to impress people but failing miserably; kind of a cross between Guy from Galaxy Quest and Roger Wilco from Space Quest. However, by the end it turns out that he committed the murder and also blew up a planet, simply because he is sick of not getting noticed, and indeed he seems satisfied at the end that, no matter what happens to him, nobody will forget his name. In other words, he turns out to be a John Hinckley-esque psychopath, willing to go to drastic measures just to get noticed. Underneath, he is not a pleasant character. He is not the cross between Guy and Roger Wilco that everyone thought he was the whole time (yet another good example of bucking the stereotype). I won’t name any names here, but both actors who have played this role so far did a great job of being the goofy, lovable ensign. But only one of them had imbued him with a sort of dark and sinister edge during the earlier parts of the show that made the reveal believable. In both runs the reveal made sense in terms of the plot and the facts about the character. But only during one run did the reveal remain true to how the character was portrayed. And that’s what strikes audiences on a deeper level.

Let’s take another example. Hope Hartman is playing Calamity Janet in the current show. At one point in the show, her beau, Jesse Joe James, ends up falling for another woman, leaving her as the scorned lover. The scene and song that ensue (where she tries coming on to him again and, when that fails, seduces the town drunk, mostly to get Jesse to notice her again, who is pointedly ignoring her the entire time) could easily be played just for comedy, with that “crazy tomboy singin’ a toe-tappin’ western tune to a goofy drunk guy”, were it not for the subtext that’s obviously going on. You can see in her performance that she has thought out her reasons for why her character acts the way she does. Once again, there is a dark edge to her that shows her vulnerability and desperation upon losing Jesse that, in the hands of a lesser actress, could simply come across as petulance. This brings her character to life and rounds her out a little bit, enough so that even in that negative review I quoted from earlier, Hope is commended for a strong performance.

Now, a lot of this is up to each individual actor’s abilities and talents. However, there is no talent that cannot be matched by adequate preparation (what I shall call the Batman rule). That is why I also say that the director can solve these problems. As long as the actor is willing to work as hard as they can to compensate for their weaknesses, and the director knows how to train and bring out those qualities (or maybe gets a good acting coach to teach them said techniques if there isn’t time), then the performances of even the most inexperienced actors can be improved dramatically. I was in Fiddler on the Roof at BYU-Idaho back in 2005, which had some top-notch actors and a very good director. I was given the role of the Russian constable, and I did my best to imbue him with subtext, turning him from a transparent bad guy who kicked all the Jews out to a man who did what he had to, regardless of his personal feelings. However, due to both a lack of acting talent/experience on my part and a lack of direction from the director (since he was busy directing all the people who had more than five lines), I don’t think I did as well in the role as I had the potential to. One of the other professors at the university basically said as much, adding that the blame for that was placed mostly on the director’s shoulders. Now, I’m not trying to absolve or condemn anyone with that anecdote, but I was simply pointing out that focus from a director who knows how to get what they want from an actor, coupled with an actor who is willing to put in the time and effort required, can turn any boring performance into something stand-out and memorable, and can change a stereotype into a person. (The problem also comes from actors who aren’t willing to put in the effort, but that’s a whole different topic.)

These ideas may help shows become more memorable and enjoyable, and lift them above Transformers-level entertainment. Now don’t get me wrong; if we’re satisfied with our current level of performance, then we don’t necessarily need to change anything at all just to try to make this more sophisticated. After all, Transformers made a lot of money, and did exactly what it set out to do: provide a few hours of entertainment and a bit of escapism. But we can do more to create characters that will connect with the audience and make them think. Some of our scripts already do this, even if it’s mostly in the subtext. And, with proper attention, time, and care, I believe this can be done without losing the entertaining and fun aspects of our shows. We don’t have to go dark to make good characters. Indeed, we can’t go too dark, since there already is murder involved. However, keeping things lighthearted doesn’t mean keeping them one-dimensional. Even if we are low art, just like newspaper comics, are we content with being Garfield, or do we want to become Calvin and Hobbes?

Will these things help Poison Ivy Mysteries become “art”? Probably not. Then again, perhaps it’s not the medium of murder mystery theater, but the quality of perception and expression of the shows and characters that determines their significance.

But what would a hack songwriter know?

Humor and Arthur: Things Looked Fuzzy Before I Got Glasses!

(note: the title of this post is from what an Arthur talking doll I had says when you squeeze him. He says some other things too, but that one’s by far the best.)

I’ve started watching old episodes of Arthur recently. I used to watch this show all the time, as recently as 2010 or so, but lately I hadn’t seen it for a while. So when I started watching the first season again I ended up rediscovering some things that I had loved but mostly forgotten about, and some things that probably had more of an impact on my own sense of humor than I realized at the time.

I discovered Arthur when I was fourteen years old and in ninth grade, and though I was still in junior high I had mostly moved on from kids’ programming (it was still two years before I could claim “nostalgia” as the reason I looked up old Disney Afternoon shows online). For about two and a half weeks I was at home and basically bedridden after having my gall bladder removed, not with laser surgery as they do nowadays, but with the old-fashioned “cut him open like a ripe melon” style of surgery. During that time is when I first watched Arthur, and since I was on a lot of painkillers at the time I still have some strange memories of the first season of that show. It was also around this time that my sense of humor started to mature from juvenile “knock-knock joke”-type stuff to more sophisticated comedy, and while Arthur certainly wasn’t my only influence in that regard (90’s-era The Simpsons was a big part of that too), and it may just had been coincidence due to the life stage I was in at the time, I think I owe a lot of my certain brand of humor to the style found in Arthur, especially in the early seasons.

You see, while I think Arthur is one of the funniest shows on TV, Arthur isn’t a comedy, or at least it’s not touted as such. It’s primarily a PBS kids’ show, where normal kids learn valuable life lessons about sharing and teamwork, etc. etc. It was one of the more subtle PBS shows in regards to its educational value (most other PBS shows were a little more upfront about exactly what they’re trying to teach), but it wouldn’t quite have fit on any network at the time either, not being a glorified toy commercial or hyper joke factory like most Saturday Morning fare (is the Saturday Morning cartoon block even a thing anymore? Has the whole paradigm of kids’ shows shifted to DVD’s and Netflix and whatever? Strangely, as a 30-year-old single childless man who doesn’t watch My Little Pony, it’s not something I’ve investigated in a while.). And since neither comedy, educational value, nor commercialism are explicitly its focus, the humor that does exist isn’t shoved in your face like a bad Spy Kids movie, but is simply allowed to exist on its own terms.

Most of the stories in early Arthur episodes are as slice-of-life as it’s possible to get. Arthur gets glasses. Arthur gets a puppy. Arthur’s family goes on vacation. Francine gets a lead in the school play, with predictable results (it goes to her head until she realizes that other people worked hard too, so they all work together at the end, etc. etc.). Nothing terribly groundbreaking. But the humor rarely, if ever, comes from the actual premise of any particular episode. The jokes are little side bits that appear and deliver, and almost immediately the episode moves on. There’s no laugh track, there’s no awkward pause or reaction a la The Office, and many jokes probably go over kids’ heads to the point where they may not even realize that a joke happened. One example of that occurs in an episode where Arthur’s family hosts a family reunion at their house. The focus of the episode is that Arthur’s mean cousin Mo will be there, and Arthur spends most of the time avoiding her, only to find at the end that she’s actually pretty cool, and Arthur’s the only reason she goes to these reunions, and they become friends, etc. etc. But every so often we get little glimpses of what some of the other relatives are like, and my own personal favorite is a certain uncle who’s trying to make it as a writer, but is clearly single, somewhat pretentious, and a total failure. He tries to impress everyone by summarizing an original story he’s writing, only to have Arthur’s great-grandmother point out that it’s just like The Fugitive, or Les Miserables, or The 39 Steps, to which the uncle stammers, “Well, yes, it’s like those, but, uh, completely different.” This would be a fun scene on its own, but what I think makes it great, and just up my alley, is that it’s not the focus of the scene (it’s just going on in the background as Arthur’s sneaking around trying to avoid his cousin). In this way the scene is allowed to be real. It’s not a standard comedy setup scene, it’s just something funny that happens in the background of life, and that makes it genuine. In a way, it’s the opposite of certain shows like Family Guy and South Park where the humor and events of the show are so completely divorced from reality that sincerity is lost, and the proscenium is revealed, so to speak. (The same uncle later on tries to get everyone in a game of charades to guess some obscure 14-century book about the bridges of Paris, and gets all huffy when nobody knows what it is. Another reason I love Arthur is because it has great adult characters; where in most kids’ shows the adults are either completely ineffectual, sadistically evil, simple authority figures, or generic stereotypes, the adults in Arthur all have their own personalities and quirks without pulling the focus off the core group of kids, and this uncle and the family’s reaction to him is a great example of that.)

On the other end of the spectrum, yet somewhat related, are when little reality-breaking surreal moments occur, but nobody pays them much mind. These are some of my favorite kind of jokes, not because they’re necessarily all that funny on their own, but many just come out of nowhere and quickly disappear again. Some gags like this include a toy that Arthur finds at a toy shop that’s based on a Transformer, except instead of turning into a robot it turns into a likeness of his principal. It doesn’t really make any sense no matter how you slice it, but it’s a tiny bit in an otherwise unrelated scene that adds to the quirkiness of the Arthur universe. Another such scene happens when Arthur is reading a story he’s writing to all his friends one by one, and they keep making him change it until it’s a confusing mess. When he reads it to the Brain they’re on the bank of a river or pond or something, and when Arthur asks the Brain what he thinks, he picks up a frog who croaks, “Rrrrrrotten,” and hops away. Nobody pays any attention to the fact that the Brain just had a frog answer the question; the scene just moves on with the Brain giving Arthur some more writing tips.

One of my all-time favorite gags like this comes in an episode where Arthur is teaching D.W. how to ride a bicycle and they’re working on various hand signals (holding your hand up means right turn, to the side means left turn, etc.). D.W. makes a silly face and waves her arms around, and asks Arthur what that hand signal means. But before Arthur can get too annoyed, suddenly a guy (who is apparently their next-door-neighbor Mr. Sipple, though I don’t recall seeing him in any other episode except maybe the one, years later, where he moves away and gets replaced with a family from Ecuador whose members become semi-reoccurring characters) wearing nothing but a towel appears out of nowhere and hands D.W. a cabbage, who explains that, where he comes from, when somebody makes that goofy face while sitting on a bike, it means, “bring me a cabbage, fast!” He then says, “I left the tub running! Bye!” and runs away, and the scene continues like nothing happened. Not only is it a wonderfully surreal moment, but it occurs in the middle of something as mundane as teaching a kid how to ride a bicycle, giving something utterly forgettable a delightful twist.

Probably the most memorable gag like this (although not the best, in my opinion, though it is pretty good) is an episode where Art Garfunkel (yes, really) is following the kids around the whole time inserting musical stings every so often, and nobody even really pays attention to him until the very end, when Arthur asks Buster where the singing guy came from and Buster has no idea. There’s even a bit where Garfunkel plays a happy, upbeat ditty about how sad Buster is until Buster gets mad that he’s not playing sad music, at which point Garfunkel plays something slower and sadder to oblige. All this in an otherwise rooted-in-reality episode about Buster coming home after a long trip around the world with his dad and having to readjust to being back home.

There are lots of other kinds of humor present in Arthur (such as the usually wonderful imagination spots), but those are my two favorite types: humor that exists on its own terms without having to draw attention to it, and humor that’s wonderfully surreal in the midst of the mundane. This, in turn, drives a lot of things I think are funny in the real world, too. For example, a shirt that I really want to get is this one: a T-shirt that simply says, in a boring font, “More information about licorice can be found on the internet.” Now, technically, it’s a quote from a random Mark Trail comic, but that’s not the point. I just love how nonchalant it is about advertising a piece of completely pointless and unnecessary advice that’s not sponsored by any licorice company or search engine. It’s a strange enough thing that you don’t have to know the reference in order to find the shirt funny (unlike a lot of nerdy humor shirts which I will not purchase), but at the same time it’s not screaming, “I’m a funny shirt! Laugh at me!” It just is what it is, and if you don’t find it funny, then who cares? At least you get good Internet searching advice in case you need to know more about licorice. The humor more comes from the fact that this factoid has now been immortalized on a T-shirt and somebody is out there displaying it like any other T-shirt. Also note: this shirt wouldn’t be funny if the wearer went around drawing attention to it. It would be annoying. But if you saw somebody wearing this at, say, the grocery store, just picking out lettuce or something as though their shirt was completely normal, even though it’s kind of surreal? That’s my kind of humor. And that’s something I could easily see happen in an episode of Arthur.

Life is full of the surreal mundane. And I like to make everyone’s day a little more surreal if I can, without drawing attention to it. I had a friend in college who told me how she really likes how I tell jokes. Normally my brand of humor is just to insert some sort of wry observation into an otherwise normal conversation, but then act as if what I said was perfectly normal. Some people say something they think is funny, but then they go around elbowing people and saying, “Eh? Eh? Get it? Get it?” or the equivalent. I just try to let the joke stand or fall on its own, and if you think it’s funny, great; if not, no biggie. A lot of the people that make me laugh deliver their humor in the same way.

I think that the things in life that make us laugh are much closer to the jokes you find in Arthur than in a lot of other comedies. People watch The Office and laugh because the situations are awkward, but you certainly wouldn’t want to actually work there (and personally, I can’t stand the brand of awkward humor in that show or others like it, but that’s just me). People watch Seinfeld and laugh at the crazy characters, but nobody would want to actually be friends with any of those people. (Invite them to parties, maybe, but not be friends with them.) That’s not to say that you’d want to be friends with everyone in Arthur (the Tibble twins come to mind, as does D.W. depending on the writer), but the characters are more based in reality than a lot of live-action comedies are (let alone other cartoons), so therefore the humor seems more genuine and sincere.

I guess that this could all be summed up thusly: The things I find funny (and that abound in many Arthur episodes) are strange, but low-key. Surreal, but rooted in the mundane. Because while some comedies stop for a laugh track, or a documentary-style interview, or have the perfect comedic setup or cutaway gag, life doesn’t. If you don’t have to point out your humor or have others point it out for you, you can start to find things to laugh about anywhere. And, for me, that’s what makes life grand.

Header Gallery

A fun new part of this new blog theme is the option to have rotating header images! Here are all the ones I’ve cooked up so far in one easy-to-view place. Can you recognize all of their origins?

(Note: the 3D one probably won’t work if you look at it in the slideshow, since it’s automatically resized, so to see that one properly you’ll just have to get lucky and see it as an actual header. Keep refreshing!)